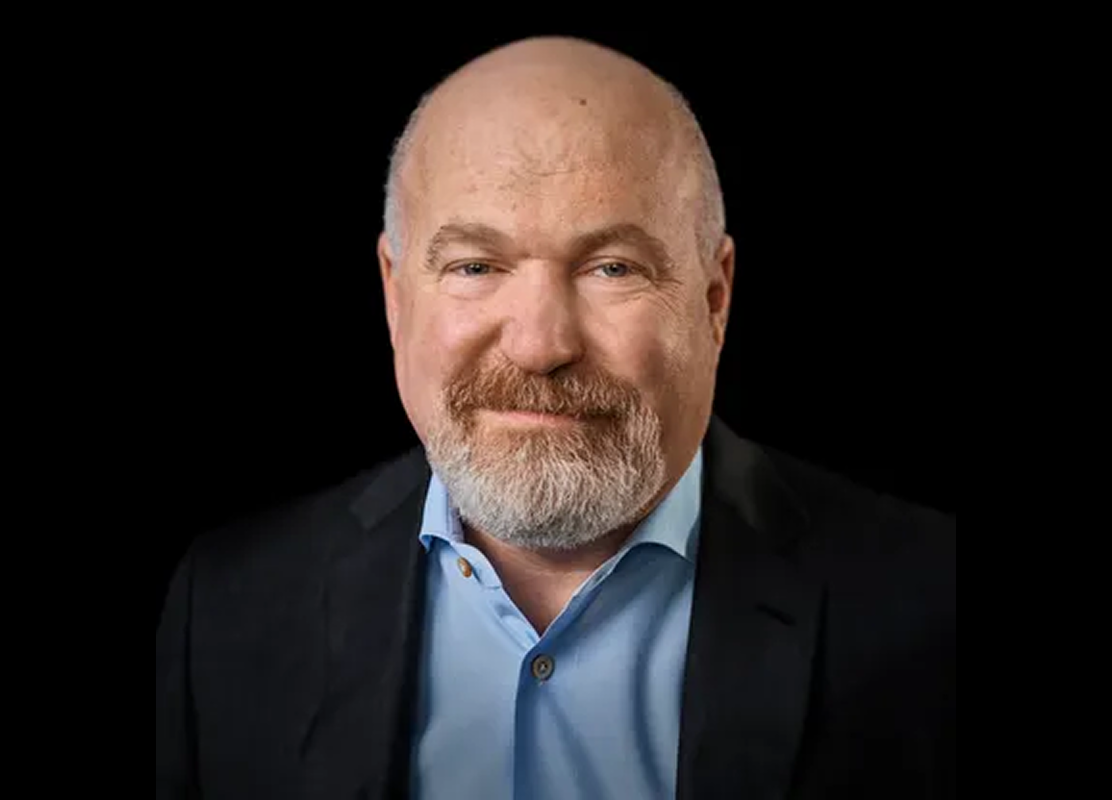

Cliff Asness: one of the greatest hedge fund managers of all time

Very few people have truly changed the way we think about markets. Cliff Asness is one of them.

Founder of AQR, student of Eugene Fama, and one of the sharpest thinkers in quantitative finance, Asness is part of that tiny group of investors whose ideas move global conversations, challenge long-held beliefs, and force even professionals to rethink what they think they know.

We talk about value, momentum, risk premia, the tension between academic theory and real-world markets, the role of AI in investing, and what it means to stay faithful to a method when everything around you tells you to abandon it.

This episode is more than an interview — it’s a masterclass in discipline, intellect, and humility from one of the greatest investors of our time.

If you care about investing, Cliff Asness is a required stop.

Trascrizione Episodio

Welcome back to The Bull, your personal finance podcast.

Aside from a few giants like Warren Buffett and Gene Fama, the person most frequently mentioned on this podcast is probably Cliff Asness, the legendary former student of Fama and founder of the hedge fund AQR, the third largest in the world.

Why is that?

First, AQR is the firm that perhaps better than any other has managed to bridge academic financial theory with real-world application.

Second, Asness and his extraordinary team produce an impressive number of papers which—at least in my case—have probably contributed to about 50% of my overall understanding of finance.

In many episodes I told you that, come what may—and even at the risk of getting hit with a restraining order—sooner or later I would manage to bring Asness here with us.

At long last, this dream has come true, and the long conversation we had—rightfully earning the title of the longest episode in the history of The Bull—adds immeasurable value to this podcast.

So, even though he will never listen to this episode, thank you to Cliff Asness for this incredible honor, and thanks to all of you—because without your presence, and without being so many, this meeting would probably have remained just a mirage.

With Cliff we have talked about his years in Chicago under Fama and French, about why markets have become less efficient over time, about momentum and value, expected returns, trend following, and much more.

Without further ado, I leave you to my conversation with this extraordinary figure in global finance, Cliff Asness.

Enjoy the episode.

…

RS:

Cliff Thank you so much for being here.

GUEST:

Happy to do it, thank you for having me.

RS

You’re gifting us an incredible privilege by attending our podcast.

You can’t know it, but I’ve mentioned you and AQR’s work so many times here that you already belong to this podcast, without even knowing it adn long before your first appearance today!

GUEST:

Okay, well, that’s a little frightening, I gotta tell you, but it’s nice to hear.

RS:

One year ago, we hosted here your Grandmaster Gene. So it’s kind of a serendipitous occasion to have you here today, somehow the stars have aligned.

GUEST:

He’s the grand master, so you’re very lucky to have had him. He doesn’t often do things like that.

RS:

Yeah. It was remarkable.

And if you don’t mind, I’d like to start right from there. Would you tell us about your days in Chicago in the eighties and 90s? Back then you had the opportunity to study finance where Modern finance was born.

GUEST:

Yeah. I mean, whenever something works out. Well, you have to admit, you got lucky. At least partially. Few, few things, have no luck involved. And just being.

I started the PhD program in Chicago in nineteen eighty eight, and it was the late eighties and early nineties when Fama and French were really starting what today we might call factor investing. I always laugh because we didn’t have these terms back then. You always use today’s terms to describe the past, even though, you know, I don’t even think we called, like, the price to book, the value factor immediately. I’d have to go check exactly when that started, but I’m going to guess their first few papers didn’t. So I got lucky I was there, I got to work with them. I got to be early in something and that. And that is a lot of luck. I don’t think anyone, certainly including me at that point, thought, oh, this is going to develop into a major part of the investment industry. So yeah, it was phenomenal and, you know, it’s not just being there. It’s studying with those two men. Gene Fama. I remember I actually wrote a fair amount, not all of it, but a fair amount of my dissertation on what today we’d call the momentum factor. And I remember being very nervous about telling Gene, I want to write on this, because, you know, everything can be argued, but it’s not a very efficient market kind of factor. I mean, some people can try to make an argument that maybe this works for an efficient market reason. It’s hard. And I think I mumbled, you know, I want to study this price momentum factor, professor. And it worked very well because if it didn’t work very well, that is the Chicago Genpharma dissertation, because a lot of investors, a lot of, you know, Wall Street looks at things like momentum. So to be able to write tons of people claim to be outperforming, but a momentum really doesn’t work. It would have been beautiful. It would have been like, you know, stock splits aren’t a miracle would have just fit in perfectly. But I said this to Gene and his response, which I had feared. Well, his response was, if it’s in the data, write the paper.

RS:

Sure. Sure. Of course. Sure. Sure. I know the response. Write the paper.

GUEST:

One thing you learn from both Gene and Ken, is not that data should drive everything. Theory and intuition. And, you know, you have to avoid just overfitting. , but they respect data. they’re, you know, willingness to acknowledge, you know, farmers many times called momentum. I think he calls it like the key embarrassment to the five factor model, or something close to that. So it doesn’t matter what you like. It doesn’t matter what result you want to see. Respecting the result you do see is something I hopefully learned. I know those guys have it. I hopefully learned it, too.

RS:

Yes. I admit that when Fama came here last year, I tried to ask him about momentum, and his response was, “It’s not worth it.”

GUEST:

He’s honest about it, you know, and and and, you know, their model forms, like the scaffolding for modern finance. It’s hugely important, but no model is perfect or right. So, you know, I admit I’ve written.

RS:

Okay. Yeah. Yeah, some are useful.

GUEST:

Yeah, I have written that I think they should include momentum as a sixth factor. You’re allowed to disagree while still admiring. But, you know, Gene’’s quite honest about it, so I’ve always appreciated that.

RS:

Momentum is a challenge for the strong efficient market hypothesis because, as you mentioned earlier, it leans more toward the behavioral side when it comes to explaining the factor premium. Now my question is, in hindsight, what was incomplete in the pure efficient market hypothesis view, in your opinion?

GUEST:

Yeah, well, I’d like to, to even back up a little bit the pure efficient markets hypothesis. , even Gene. I don’t think he’d say markets are perfectly efficient. I think some, sometimes people overstate it, and they want to, you know, if someone believes markets are close to efficient, they’re they’ll paint Gene as more extreme than he is. I sat through his introductory first year PhD class three times, once as a student and twice as a teaching assistant. I went to every class because I was terrified to get something wrong. And, you know, sometime after teaching what the efficient market hypothesis is, Gene shocks the class by saying markets are almost assuredly not perfectly efficient because. Because Gene is brilliant and sane. Perfection is a silly hypothesis. I think Gene probably thinks they’re more extreme. More efficient than I do these days. I think I probably think they’re more efficient than the average day trader to go to an extreme. I don’t think most of us who are paying attention and trying to get the details right would have ever argued a pure, efficient market hypothesis. I do think, and I know you know the literature. Well in the ridiculous amount of years since then, I make a lot of comments about how old I feel when we go over these, these nineteen eighties kind of stories. Thirty seven years ago when I first met Gene. It’s been a long time, but in that period, a lot of empirical and theoretical results have tested, and you accurately talk about an efficient market explanation versus a behavioral one. We’re still fighting about almost all of them.There’s always going to be a story in one direction. You have to make a judgment on each one. Which explanation, you know, makes more sense to you?

And I think you’re right. Momentum is not impossible, but is much harder than some of the others to tell in an efficient market if a characteristic says this portfolio of one thousand stocks around the world should beat this other portfolio or does beat this other portfolio. There are always three possible reasons that can be true. One is accidental and overfitting. It just happened. It’s not going to happen again. Someone wrote a paper on it. If you get past that and I think, you know, certainly this is self-serving, but I think things like the value effect, the momentum effect now have such overwhelming evidence in so many places. I don’t give that a lot of credence, but you always have to have to have that one. So if something is real, it can work in an efficient market sense, because those things that outperform are riskier and you have to get paid for taking risks. And we could go down a rabbit hole of how to define risk. That is not simple either and is part of the issue.

But the other reason something can work is someone’s making a mistake. It’s not that these thousand stocks are riskier than these other thousand stocks, or the portfolio of them, to be more precise, is riskier. It’s that on average people overpay or underpay or something like that. And I do think again, to your point, momentum falls. It’s very hard to come up with something other than a behavioral explanation for moment of momentum would say value investing. It’s, , I think it’s closer to a battle. I admit, I’ve drifted more to the behavioral side over my career, but it’s still an interesting argument. It’s not a gimme either way.

RS:

Mm. Yeah. Definitely.

Last year you wrote a widely cited piece, The Less efficient market hypothesis, where you claimed that markets have become less efficient over time. Long story short, you do feel markets are still pretty efficient, at least for the average investor, but not that efficient as they used to be.

Could you please walk us through all of that?

GUEST:

Yeah, sure, first, I hope Gene’s not listening. I’m still scared of him when I say these things.

RS:

Do you still feel guilty for trying to beat the market?

GUEST:

Yeah, that was in my bio for a while. I don’t know if it’s still there. I’m scared that I’m trying to beat the market because Gene’s going to yell at me or something. Let’s go back to this, this idea that everyone who’s thought about it would agree. I think that markets are not perfectly efficient. Once you accept that kind of simple concept. Two questions. How inefficient are they and does this change through time become legitimate? Right. If things are not perfectly efficient, the you don’t know how inefficient they are and the idea that they will always stay the same amount of inefficient, it strikes me as kind of silly, so what I’ve observed over my career and I admit doing this stuff live and suffering the slings and arrows of some periods. where some of these factors we’re talking about were not rewarded. That is actually kind of a mild way to say viciously punished, two periods in particular, the what’s often called the dot com bubble in the late nineties.I say often called because if you just called the dot com bubble. You’re kind of giving away the story, because you’re using the bubble word. Not a good genpharma word. Right? If so, if you think it was a bubble, You know we wrote a lot on this at the time, and we revisited it over the years. If you take the basic Fama and French value kind of work, and you could do much more subtle versions of value than just, you know, book to price. But you see the effect no matter what you look at, a strategy based on buying cheap and selling expensive got crushed for about eighteen months. Like, you know, two and a half standard deviations, three standard deviations, kind of crushed, not ten standard deviations. We’re not talking about Nassim Taleb, Black Swan. Are there better or worse ways to measure this? But at least to my knowledge, to that point, no one had asked about how different the pricing was. Let’s keep it simple and just do a Fama-French price-to-book. Most people, including us, measure value a little differently these days, but if you sort stocks on price-to-book and go long the low multiples and short the high multiples, we thought an interesting question was: how different are the multiples? Does that change through time, and does that have predictive value? What we found was obvious: if you do this sort, the expensive ones always look higher-multiple than the cheap ones. I like to say your spreadsheet is broken if that’s not the case. The ratio, from memory, varied between three and six over time. The top third of more expensive stocks were sometimes about three times the price-to-book of the cheap stocks, and at the peak of the dot-com bubble they got up to about six times—again from memory, about twelve times.

RS:

Yeah. Crazy. A little.

GUEST:

Nothing similar had ever occurred before in fifty years of data. It was one of those embarrassing graphs; clearly something was going on. You could tell an efficient-market story where our measurements were missing something, or that the world had gone nuts. We also showed in that paper, which we still believe today, that these things are very hard to time. I wouldn’t bet my life on it. Even a few years ago I called it sinning to time these factors, and said you should sin occasionally and modestly. But over the long-term data we had, in the three-to-six range, when it was more extreme, value did better over the next few years and vice versa. That could have an efficient or a behavioral explanation. So at twelve, it looked pretty good, and that did work out. I did think that was a bubble; I didn’t think that was an efficient-market story. I wrote a piece called Bubble Logic in early to mid-2000 arguing this.

RS:

Good call.

GUEST:

I said: I don’t know how to define a bubble, but here’s my definition: if I can’t come up with assumptions in the ballpark of what I think are realistic that justify these prices, I’m willing to use the bubble word. In my view at the time, on very diversified portfolios, I would never use the bubble word lightly. Some people are promiscuous in how they use it, but for me a bubble also has to be market-wide and pervasive; it has to be about diversified portfolios, and this fits the criteria. If you had asked me back then to project forward into the next few years, say 2003–2004, I could have bragged that we had been right. The “round trip” was very profitable for us, even though we didn’t enjoy the first part at all. Those eighteen horrible months for value also happened to fall between the second and nineteenth month of my new firm, so that was not remotely fun. Momentum, during that period, did reasonably well, but not well enough to offset the disaster in value. We had argued that things would go very well afterward, and they did: the round trip was excellent. But if you had asked me after that full cycle, “Do you expect to see something this extreme again in your career?”—thank goodness no one did, because I think I would have answered incorrectly. I would have said highly unlikely. It had been the most extreme event in fifty years. And the question “in your career” implicitly assumes that you and your peer group are all still around. And if you’re still around, you’re probably the ones in charge. How could something like that happen again after you’ve already seen it once and are now the senior generation? I would have said no, very unlikely. And yet it happened again. Even before COVID—so roughly late 2019—the same kind of measure, done simply on price-to-book (though today you can use more diversified metrics), had come back very close to tech-bubble levels, with value suffering in a very similar way. And then, perhaps exceptionally, COVID hit and everything got worse. We blew past the extremes of the tech bubble in the spread between cheap and expensive stocks.

RS:

Me lo ricordo. Sì. La demo.

GUEST:

There was that absurd six-month period when the only stocks anyone seemed to “want to own” were Peloton and Tesla. It was not a pleasant time for people building systematic portfolios based on the value effect. So it happened again, and we survived. In fact, we ended up making money over the whole cycle, but it was extremely unpleasant for quite a while. Separately, we believe we’ve made our process more robust. If it happened again… even if we hadn’t made changes, we still love our process: it worked. It just wasn’t fun to live through. After the second time, the old phrase “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” applied. I was fooled twice, so shame on me. This made me ask: what did I miss? If I’ve lived through two bubbles in my career that were more extreme than anything seen in the previous fifty years, what hadn’t I understood? I started accepting again the empirical fact—which some may contest—that I had lived through two episodes I would call bubbles, more extreme than anything in the earlier data. I began to wonder why. And the piece I wrote, The Less Efficient Market Hypothesis, does not claim that markets are wildly inefficient or easy to beat, but that they are less efficient than they used to be.First of all, I wish I could correct something in that paper: that’s what I had in mind, but I don’t think I stated it as clearly as I could have. You always want to rewrite part of an old article. I even try to avoid reading them—or, no offense, listening to podcasts I’ve appeared on—because I just think, “Oh, I could’ve said that so much better.” The only time I listen to a podcast I’ve been on is when I have to go back on it, because I don’t want to tell Riccardo the exact same stories. But I started asking myself: why? If markets aren’t perfect and are subject—not necessarily to being less efficient every single day—but to being more prone to these episodes of “madness,” if you believe, as I do, that they were bubbles, then you have to start asking why. And in the piece, I hope I’m very clear that I’m making a hypothesis. We have two episodes. I like to joke: as humans we see too many crazy episodes in markets. As statisticians we see far too few. Give me a few hundred bubbles of comparable magnitude and maybe I can start telling you something statistically reliable about them and really test hypotheses—figure out what caused them. Two is not a big number to run tests on. But they happened. So I have a few—actually my two favorite—hypotheses, which I believe in.

I’m soft-selling it here. I’m trying to admit that I cannot be certain — they are guesses — but I do believe in these guesses. The first is a very well-known one: the rise of passive indexing. I’m not a passive hater. There are people who think passive is just Satan and has ruined markets.

RS:

Yes, I know one. Absolutely. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.

GUEST:

I know more than one, and some of them are brilliant people — they’re just quite extreme on it. I think passive has still been an incredible enhancement for the average individual. Jack Bogle and his like are heroes to individual investors: being able to get the market premium for no cost. But we all know — well, I think anyone who’s thought about this would agree; let me say it that way, the whole world doesn’t know this — we can’t all be 100% Jack Bogle, market-cap–style passive. Jack Bogle agreed with this. We had a podcast for a few years — because, I don’t know about Italy, but in the United States, I believe legally everyone must have a podcast at some point. Maybe we’ll start it again one day; it was kind of fun. Some episodes were internal, but we also had guests, and I was extremely lucky to get to know Jack very well. He agreed to come on our podcast. It was a bit of an odd-couple thing: long–short, levered hedge-fund quant and Mr. Passive. But we actually agreed on a lot. He came on and we got into this discussion about how the whole market can’t be passive. And Jack absolutely agreed with that. He thought — and he’s probably right — that for the marginal investor, where we are today, the move to passive is still a good one. But he absolutely agreed it can’t be 100%. Jack was a very intellectually honest guy. And I asked him: “So, Jack, what fraction could it be?” And he said: “85%.” And I said: “That’s fascinating, Jack; where did you come up with that?” And he said: “I made it up.” Because no one knows. And the point — which I think Jack was trying to convey, and I’m trying to convey now — is that we know the market gets really weird, and it’s even hard to think about what everyone being passive would look like. Literally, no one’s thinking about prices. Who says the Magnificent Seven are worth more than the corner drugstore if literally nobody is doing it? Passive is a free rider. Passive free-rides on people doing the work. And if everyone tries to be a free rider, you get a perpetual-motion machine. So I think we know that at 100% passive — and still, finance people like me love to steal analogies from physics because it makes us feel smarter — I call this a singularity, a black hole. The regular laws of physics break down. We don’t know what 100% passive looks like, but we know it’s really weird. And it’s unlikely that all of the weird happens between 99% passive and 100%, right? So if you have fewer people thinking about what stocks are actually worth and more people trying to free-ride on those who do, the idea that prices could be at least a little less tethered to reality and a little more prone to these episodes strikes me as pretty reasonable. Again, passive is awesome. I don’t know exactly where we are on that curve where things get weird — it’s just a hypothesis. I know we have a lot more passive today than we used to. It’s hard to even count how much. There’s direct passive — that’s not hard to count — but what about very low–tracking-error portfolios? If you’re doing that, then you’re mostly passive.

RS:

The closet indexers.

GUEST:

Yes, so we know we have much more passive than we used to. I think that’s a contributor. But that’s not my actual best guess.

And I still— sorry, go on. Please, Riccardo.

RS:

Yes sorry, I just wanted to ask you a question about it before you move to the second hypothesis for the markets being less efficient. Am I wrong if I claim that under the Grossman Stieglitz paradigm, the market should always be in some kind of equilibrium? Because too much passive investing, whatever “too much means”, should create more opportunity for active investors to outperform the market, which in turn would lead to a reduction in the overall market’s passive share.

GUEST:

Yeah, I think there is some truth to that. But a few things. First, I love a term from Ken French, though I’m not sure if he coined it; he modestly says he stole it from someone else, but I forget the origin. The term is “there’s an efficient amount of inefficiency,” which I love, because it sums up what you said: there may be inefficiencies, but people will take the other side and reduce them. It’s still a paradox, though, because nothing escapes Sharpe’s arithmetic that the average can’t beat the average. One of my partners, Lasse Pedersen, has argued—and I think he’s right—that new issues not in the index may be a small end-around, but magnitude-wise that doesn’t make a big dent in the Grossman-Stiglitz paradox, which I think is deeply tied to Sharpe’s arithmetic. Except for new issues, a small part, we’ll never have a case where the average active manager wins. By average active manager, I don’t mean a particular class like mutual funds or ETFs; I mean anyone deviating from market-cap weights. If you sum them up, for everyone overweight there’s someone underweight.

RS:

Okay, Yes, absolutely.

GUEST:

So when you argue that more opportunity should attract people who make inefficiencies go away, you have to argue for informed and less-informed investors. The sum will always equal the market. But there may be times—maybe these bubble times—where the rewards to being the active person going forward are high, though it’s usually painful getting there, because bubbles don’t occur in a day. Things are fine until suddenly they’re not. If anyone were smart enough to avoid value investing until March 2000, the dot-com peak, and then put on a huge value bet at that moment—more power to them. You have to ask whether there are times when certain classes of investors… and there’s an inherently arrogant act in being an active manager. It says: I’m going to be on the right side of Sharpe’s arithmetic. The Grossman-Stiglitz paradox might hold, but there are losers and winners, and I’m going to be the winner. I am, in fact, that arrogant. But being honest, that’s what anyone trying to beat the market is also saying. So I think there’s an ebb and flow. When things are crazy—accepting, though some would argue, that bubble periods exist—there are always two problems with active strategy: deciding what to do, and sticking with what to do. The second one becomes much harder in real life with investors using other people’s money who will yell at you. That gives a different perspective than when I was just writing papers. If you accept that there are times when things get really irrational, these bubbles are easier to identify—extremes are easier to identify—but harder to stick with. These two episodes I used were one and a half years and two and a half years long. To a statistician, that’s not long. To a money manager, especially two and a half years, it’s an eternity.

RS:

An eternity.

GUEST:

it’s an eternity. Sometimes I talk about behavioral time and statistically valid time having a big disconnect.

Managers like me complain too much about this because we don’t want a perfectly efficient market. If we believe what we do works because of behavioral biases, a perfectly efficient market—besides being a logical absurdity—would leave nothing to do but take extra risk. Maybe there is some of that, but much of what we do works because of behavioral factors. Everyone who thinks markets are imperfect wants big episodes of craziness that we somehow don’t suffer from: we put on the trade and the market immediately wakes up and rewards us. It doesn’t work that way.

If the market is more prone to bubble periods—and I’ve given you one of my two stories for why—it will be easier to say “this is crazy,” but harder to stick with, because the losses incurred on the way are larger and last longer than in the past.

Maybe some theoretician will tell me, “No, that’s in my model.” But every theoretical model I’ve looked at — utility-based, whatever — I have not seen duration of pain in them. They tend to be about levels of wealth. I haven’t seen a ticking clock in those. And again, as a real-life money manager, you can make up the numbers, but I would rather face one and a half times the magnitude of a tough period — a so-called drawdown in returns — for six months, than two-thirds of that one and a half over three years. Over three years, you’re going back to your investors at the end of year three. And our longest has been about two and a half. So we’ve glimpsed this — we’ve never seen three. But at the end of one year, especially if you have a reputation and you’ve done well over time, your investors are pretty calm. They’re like, “Ah, it was a bad year.” Very few — unless you’re Jim Simons with the Medallion Fund — but everyone else has a bad year occasionally. At the end of year two, you’re getting the side-eye pretty hard. You’re losing some investors. At the end of year three — which, again, thank God, I haven’t quite had to live through, but I’ve glimpsed — even though in these cases you are more right than you used to be, you tend to be suffering from the same things that got you there after year one and two. But that’s part of the problem. You go back to an investor at the end of year two, which I have experienced, and it’s the same story you said at the end of year one. You’re basically saying, “Well, it happened again.” And in fact, it did. And it is better going forward. But all kinds of weird things happen — a lot of agency problems in our world. You might have been hired by a team that likes what you do and understands it. But if you’re having a second bad year, you’re often not even talking to them — you’re talking to their boss, who didn’t hire you and might be brilliant but has no idea what you do. You might end up — God forbid — talking to the corporate treasurer. So the staff of the pension fund hired you, and two years later it’s like, “This is ugly. You should be talking.” They don’t cut you a lot of slack. So I think duration — sorry, it’s a long rant — but I think a model that includes duration of pain is an interesting one. It may be exactly proportional to magnitude; it may not be.

So yeah, I think markets have gotten crazier, and I have a few theories as to why.

RS:

Yeah. Okay.

If I’m not wrong your second guess as to why the market has become less efficient has to do with stuff like gamification of trading, market noise induced by social media and other things of the like.

GUEST:

Yeah, absolutely. And look, on this one… I mean, I’m turning sixty next year, so lately I’m a little obsessed with age. I sound like that cliché old man yelling at kids to get off his lawn. “It’s the kids with their social media and their apps and all that.” But anyway—if we’re talking about markets, you always have to start here: if markets aren’t perfect, if they occasionally drift into extremes, something must be pushing them there. Markets aren’t pure arbitrage machines; they’re voting mechanisms. Ken and Jean have that great paper on tastes and disagreements. Others have said similar things. Think again about that simple example: there’s a big mispricing, and you have uninformed investors doing something silly while informed investors take the other side. If the mispricing is way out there—and imagine me holding my hands apart to show it’s big and diversified—you can build a portfolio that you’re pretty confident will make money from the arbitrage. Not instantly, maybe over a year or two, as capital slowly comes in to lean against the extreme.As that happens, the mispricing shrinks. Now imagine it’s half as big. It’s still maybe attractive, but it’s half as attractive. It hasn’t been pushed all the way back to rationality, but halfway. And now there’s half the profit left, and the people already in the trade find it riskier to add more—they already have a lot of exposure. So markets, as long as there’s a net error that isn’t canceled out by some lucky opposing error, will keep some inefficiency around. Arbitraging errors is risky, and that risk only fully disappears when the mispricing disappears—which rational investors will never push it to. They make errors smaller, not zero. That’s why I say markets are voting mechanisms. You vote with your dollars. It isn’t a fair democracy—Buffett gets more votes than I do, and I get more votes than the average person—because dollars move prices. Now, this is where I come closest to politics, Riccardo… which is dangerous ground these days. But I think most people—not all, but most—would agree that the whole social media environment, the bubble we all swim in, has made our politics worse. People live in informational echo chambers. Social media enhances confirmation bias. Algorithms—whether it’s TikTok, YouTube, whatever—tend to push you toward more extreme versions of whatever you already believe. And I’m not taking sides here; I’m saying the structure of the system pushes you toward extremes. So if markets are voting mechanisms, why wouldn’t something similar happen there? I can’t tell you the exact magnitude. I can’t tell you how this interacts with indexing. My best guess—totally a guess, very un-quant of me—is that this social-media-driven dynamic is a big piece of the story. When you don’t have clean data, you’re stuck with observations. Then comes gamification. A lot of retail investors are just… having fun. And I know I sound like a grumpy old man again, but I don’t think it’s an accident this stuff took off at the same time as legal sports betting in the U.S. People sit on their phones, open the Robinhood app, do whatever crazy thing everyone else is doing, it works for a while, and then confetti literally rains down on the screen. Compare that to betting whether a basketball player makes a free throw—it’s basically the same dopamine loop, just dressed up as “investing.” Am I an elitist who suspects a lot of these people aren’t doing deep research? Yeah, I kind of am. They might be brilliant at things I’m clueless about. But in markets, I don’t think they’re doing rigorous analysis. And this environment… it makes markets more prone to extremes. If I wanted to cheat, I’d point to the meme stocks. The U.S. went much further down that road than most other countries. Meme stocks are the cartoon version of what I’m talking about: almost entirely driven by social media and online trading, and almost certainly irrational. It’s unfair to point to the most extreme example and say “see, that proves everything,” but it’s clearly on the same spectrum. And I think the whole market has become more meme-like, or at least more capable of becoming meme-like. As 1990s Cliff would yell at 2025 Cliff for saying this… but I think it’s true. One more thing I didn’t finish earlier: Grossman–Stiglitz implies that part of the market is always taking the other side of irrational behavior. If my hypothesis is right—and again, big ifs—what’s happening now is this odd kind of fairness: when markets get crazier, the opportunities for rational investors get bigger. The problem is sticking with them. It’s easier to spot the inefficiency, harder to hold the trade. A perfectly efficient market offers no profits. We want inefficiencies. We just want them to shrink right after we put the trade on. So if I’m right, any kind of rational investing—Fama-French, traditional Graham-and-Dodd, anything that systematically compares price to fundamentals, growth, moats, risks—will make more money long-term in a market that’s grown more extreme. But that “if” becomes larger, because sticking with it is harder. Which is why it’s oddly fair: the extra return only exists because it’s harder to earn. If it weren’t harder, the opportunity wouldn’t exist. So yeah, I think markets today are more prone to extremes. And that’s a good thing if you’re on the rational side and if you can stick with it. Two big ifs.

RS:

Yeah.

Nowadays there’s a huge debate about at what point of the cycle we find ourselves with those very high, bubble like stock valuations. Although fundamentals seem better now than those back in 1999. Anyway, though it’s hard to make predictions, it’s always important to make capital assumptions about future returns, in particular at this seemingly late-stage secular cycle. Cycles have a mix of rational and behavioral explanation behind them. You can see here Antti Illmanen’s second book about expected returns. And you all at AQR did a great job trying to explain and make sense of expected returns. My question is: in your opinion, how much does it come down to rational variation of risk premia and how much is more behavioral when it comes to explaining why expected return changes over time?

GUEST:

Well, you give me a chance to give Antti a plug. Antti and his colleagues have a ten-part series on our website about forming long-term expected returns.

RS:

Wonderful series!

GUEST:

I’m on social media; I announced this morning that the tenth part is out, and I think it’s the final one. Obviously, Antti is one of my business partners, so you should discount what anyone says in that direction, but I’ve loved his work since I met him in 1988, and I think that series is great. I’m partly filibustering here because it’s a very hard question to answer. This debate has been going on forever. When they split the Nobel Prize between Fama and Bob Shiller — Lars Hansen also got a share — Shiller and Fama were juxtaposed; Lars was doing other work. Gene did a lot more than this, and Bob did much more too, but a substantial reason Bob got the prize was the notion of excess volatility. This debate has been raging for decades. Fama and French, in the ’90s or maybe the ’80s, wrote pieces saying there is some predictability to long-run stock returns. I don’t want to overstate it.

RS:

With low expected returns going forward and given that the macroeconomic regime might have changed in 2022, after 40 years of declining interest rates and the inflation comeback, now the typical combination of stocks and bonds doesn’t seem to be an ideal one any longer. And this makes the case for further diversification in the future. You have written a lot about alternatives in portfolios, with one of them being trend following.

Trend following had a terrible decade in, in twenty tens, if I’m not mistaken, and a great year in 2022, this year so and so, but you are a strongly proponent of this strategy, as far as I understand.

The question is: would you please tell us about it? Why does it works, pros and cons, etc.?

GUEST:

First I gotta be honest and say if I think I have a way to add value that’s not very correlated to markets, whether the markets are expensive or cheap, I’m always going to want to add at least some of that. would readily admit that when markets are offering you less long-term, my excitement level about an uncorrelated source of return might be higher. So your point is well taken. On trend following, I’ll differ slightly. I wouldn’t call the 2010s terrible; I’d call them disappointing. Most versions made money — just far less than the stock market. Of course there’s heterogeneity, I can’t speak for everyone, but the way we see it, they had small positive returns, which can be frustrating to stick with when everything else is going up. It was a very painful decade for the trend-following industry. But real strategies and markets can have ten-year bad periods, let alone simply not making a lot of money over ten years. The idea of a trend-following strategy — I wrote a dissertation on price momentum for picking individual stocks. Even though I wasn’t thinking of it as a hedge fund strategy at the time, you go long strong price momentum and short relatively weak momentum, and there’s a premium to that. You make money in directional markets: stocks, bonds, currencies, commodities. You’re not going long and short within the market; you’re looking at the whole market, typically implemented with futures. Price-trend strategies are basically momentum. The same momentum strategies we talk about in individual stocks — but in the managed futures or CTA world, it’s called trend following. I can’t explain why, but I’m hostage to popular vocabulary like everyone else. The reason we think momentum or trend following works is behavioral. My favorite explanation is underreaction: news comes out, prices move as you’d expect — good news raises prices, bad news lowers them — but people anchor to prior beliefs and don’t adjust enough. So prices don’t fully reflect the news. If that’s true, then whatever has happened in the past has probably underreacted a bit and will tend to continue, at least statistically. Not in every case — which is why a systematic strategy does this across many markets. An embarrassing point is that another popular explanation is overreaction: inefficient, bubbly markets with positive feedback loops — things go up, more money pours in, and they keep going up. The hard part is that, empirically, both can be true. They sound like opposites, but they’re really not. They can both be part of the market structure, and which one dominates can vary over time. I tend to think underreaction is the bigger reason why momentum or trend works. And when I say “works,” I always mean it like a cautious statistician: it works a little more often than it doesn’t. So you want some in your portfolio.

Now, the interesting part. A trend-following strategy — the classic way to do it (and here I’ll brag a little, because I think we’ve improved on it) — is in the four big markets, usually using signals from the past month to a year: go long markets that are doing well and short markets that are doing poorly, across stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities. Different trend followers can, and do, fight endlessly about whose system is best. What lookback period do you use? Straight returns? A moving average? A more complex mathematical filter? Sure — but essentially they were all doing similar things, including us, for much of this period.

Why is this attractive? Two reasons. First, on average, we believe it works. Sometimes it gets crushed — if everything is fine and a meteor hits, there’s no trend to follow. There are tough periods for trend following. There are long stretches, like the 2010s, when trends don’t pay off as they normally do. Even then, I’d argue it wasn’t a disaster — it just required patience. But on average it pays you, and it has paid us over our whole live experience and over long-term backtests. Reason number two — and this is not a guarantee, I want to be careful — is that on average trend following has had some of its best periods during major equity drawdowns. When the world is suffering — and you mentioned 2022 — trend following was very strong. It’s only one big data point, but it’s another example of it doing its job when you need it. Again, it’s not crash insurance. It didn’t suffer in March 2020, but it didn’t help much either when COVID hit out of the blue. But those events reversed quickly. The biggest hits to investor wealth tend to be sustained drawdowns; the biggest behavioral mistakes also tend to happen in sustained drawdowns, when investors can’t take it anymore and capitulate at the worst moment. Trend following has historically done particularly well in those environments.

So the combination of something that works on average but tends to step up when needed is attractive, especially in today’s market — more expensive than average, and, perhaps (and this is less purely quant), where geopolitics may worry you more. Again, to be honest, I’ll always tell you to have some trend following because I believe in it long-term, and I don’t think you can easily time when it will or won’t work. But right now, I probably like it a little more — with the honest confession that this is less pure quant and more market observation. I also said that the world has moved on — especially our world. How we measure trends has become more subtle. It’s not just price. It’s all the news that prices are supposed to reflect. If markets tend to underreact, you can measure that through prices, but also through the news they should react to: earnings for individual stocks, GDP releases for global markets. If that news tends to move markets, then markets will underreact both in price terms and in news terms. So now we measure trends roughly fifty-fifty using both price and news, and that change has helped a lot in recent years. Another change is that we do trend following in many more places than we used to. I kept referring to the big four — stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities. What I didn’t say is that most trend followers, including us until about seven years ago, did those mostly in big, liquid markets. It turns out there is much more to do. There are many commodities that aren’t the big, liquid ones — not crude oil, but hundreds of others — and collectively they have decent capacity, and trend following works there too. There are structured trades: traditionally, every trend follower includes the 10-year Treasury (or its global equivalents). But with some thought — you have to be a bit clever — structured trades like the shape of the yield curve, tens versus twos matched for interest-rate sensitivity, are very well suited to trend following.

Even equity factors — value, momentum, quality — tend to trend. And if you’re a CTA who can trade individual equities effectively, you can capture that. These more esoteric trends, the nontraditional ones, have helped significantly in the post-2020 period. In 2022, all these kinds of trend following finally paid off after, as you said, a tough decade. Since then, it has been particularly important to diversify how you think about trend beyond just price trend, and to do it in more places. Some of the more esoteric areas — including off-the-run securities and more structured trades — have been considerably better than the traditional big liquid ones.

RS:

From the investors point of view, it’s behaviorally challenging because investing in stocks is typically negatively skewed, while investing in these strategies is positively skew. So most of the time they go meh and all the payoff is concentrated, which makes a very difficult investing style to bear for the typical investor.

GUEST:

Yeah, no, exactly. I think everything is difficult in its own way. Negative skewness can certainly be difficult. We used to worry a lot more—maybe the markets have wised up to this—about people panicking about crashes and so on. I think the “stocks for the long run” argument, the “buy the dip” idea—I kind of hate that phrase, and my colleagues have a paper coming out showing there’s nothing special about when a dip is occurring—but that attitude maybe has made markets more resilient to negative skewness. But that has been a challenge over time. The challenge with a positively skewed, positive expected return strategy is patience, because there will be long periods—although we think we’ve improved this with the two changes I mentioned—when traditional price trend in the major markets, even if it’s as good as it was over the prior fifty years, goes through long stretches where it tests your patience waiting for that big payoff. And that can be challenging in a completely different way. Again, I always come back to that paradox: I’m thankful for these challenges, because if they didn’t exist, the opportunity wouldn’t exist. That’s the case with almost any systematic opportunity. If it were easy, the easier it is to do, the more arbitrageable it becomes and the more likely it is to go away. But yes, I think there are ways to improve it—ways to make the average return better during those fallow periods for traditional trend following. Still, even if you told me, “AQR, you can’t use either of the two big enhancements you think have improved things over the last five to ten years,” I would still want some traditional price trend in my portfolio. And yes, it would still have the problem of relatively long periods during which you have to keep apologizing for it.

RS:

Sì. Sì.

Prima che tu rispondessi alla domanda sul trend following, hai menzionato il value come un consiglio sensato in questo periodo.

Una cosa che ho imparato da te — e che Dio ti benedica per tutto il materiale che pubblicate! perché abbiamo imparato tantissimo sul factor investing e non solo grazie ai paper di AQR — dicevo, una cosa che ho imparato è che il value funziona meglio insieme al momentum, il che è controintuitivo a prima vista perché sembrano stare ai lati opposti dello spettro.

Il momentum implica trend. Il value implica ritorno alla media.

Consiglieresti ancora di combinarli in portafoglio anziché concentrarsi su un solo stile fattoriale?

GUEST:

Yeah, certainly. I think—you know, I wrote a paper with Laci Peterson and Toby Moskowitz called Value and Momentum Everywhere. This result was actually very consistent: the strategy works all the time, and they’re fairly negatively correlated most of the time. You get rare instances where they can be positively correlated, like a year after a giant bubble when value has been strong and has momentum, but most of the time they’re fairly negatively correlated on net. The data in my dissertation—which wasn’t as well thought out, since I wasn’t thinking of it as “I’m going to do this investment strategy”—included both value and momentum. The data ended in 1990, from 1963 to 1990, a full sample of twenty-seven years. We now have thirty-five years more. Again, you know you’re old when you have more out-of-sample data than you had in-sample data when you wrote the paper. And I would say, broadly, looking globally, I think it’s held up better than many think. Value in the U.S. has been disappointing. It’s been better globally. Momentum has been good on the net. Both have been lower than backtests, but I’m pretty sure we were saying back when we started our group at Goldman Sachs in 1994: no one should expect a full backtest going forward. We discounted those and said, “If we get half of this, we’re thrilled.” And it has certainly delivered that. I’ve also written that I think value—even in the U.S.—is underestimated a bit. I wrote a piece on our website called The Long Run Is Lying to You, showing that even over fairly long periods, if a strategy or market has gotten markedly more expensive or cheaper, your estimate of how good it is will be off if you’re just looking at returns. Because if a strategy has gotten much more expensive—if a stock market, for instance, started at a Shiller RSPE of ten and ended at a Shiller RSPE of forty—that’s going to make returns over that period substantially better, even over a thirty-year period. You do not want to, in my opinion, rely on realized returns over that period. You want to adjust for the fact that you don’t expect that valuation change again.

And while it’s well off the peak at the end of COVID—when the spread between cheap and expensive stocks, the so-called value factor, reached its maximum ever—last I looked, it was still in the high seventieth percentile. It has not gone back to fully average, and that still has a substantial negative impact on even twenty- or thirty-year returns. So I don’t believe you should expect to get the 1963–1990 backtest going forward. Backtests will always overstate what you should expect. But I think real-life returns to value strategies since then, particularly in the U.S. where those spreads are still wide, probably understate what you should expect going forward, because we’ve still suffered a capital loss on them. So, yes, the system has made money, and I think it’s at least a little underappreciated going forward. Yes, I still like value and momentum. When in my life I’ve strayed from it and been a more pure value person, I’ve generally lost. My prime example—and I do a mea culpa on this—is that in late 2019, I wrote a piece saying, “We always say timing these things is a sin. We’re going to sin a little. We’re going to do more value than normal given where the spreads were. Here’s the logic.” And I don’t think my logic ex-ante was terrible. Yes, on average you should wait to see some momentum or trend; you want both. But singular events like a bubble don’t always let you rely on the average—you have to bet on the single instance. If you’re reasonably sure that these valuation ratios will come back to some semblance of normal, even over five-plus years, you risk missing it. Just because on average something tends to trend doesn’t mean this time it won’t come back really quickly—too quickly for trend to pick it up. So at the time, I thought it was a rational bet. I still think there’s a case for it. But I will admit: once again, value plus momentum or trend did better than I did. And we did very well. But had we waited another year—a year and change—to see it start to work, we would have given up some of the inflection point when things started to return to normal, but the round trip would have been better. So once again, I should have listened to my dissertation more. So yes, I still believe in the system.

RS:

Yeah. Mm. Thank you so much. Great lesson in a nutshell.

RS:

Last question, because I’m afraid we are running out of your time.

AQR strategy has always built upon strong theoretical foundations, like academia findings put to work into the real world. But over the years, you have tended to lean more toward data, machine learning, ecc., in an effort to balance economic theory and what the data tell you. I suppose AI is going to have an impact on your strategy and your modeling even further. Would you please walk us through about how you balance finance theory and data driven findings?

GUEST:

Sure. I have said this publicly, and it’s actually been overstated by some. Historically—particularly yes, even before machine learning—if we were fifty–fifty between theory or “story” (it doesn’t have to be a very formal economic theory, just an understanding of why something works) and data that shows it works, we always wanted both. The Capital Asset Pricing Model is a beautiful theory: the only risk you should be paid for is market risk because it’s diversifiable. It simply fails everywhere we’ve ever tried it. So theory alone doesn’t get us there. Data alone—I will admit—even historically, even before recent times, even giving fifty–fifty weight to both, you could still give some weight to purely data-driven findings. I point to people like us, and even Fama–French, who believe in the profitability factor. I’ve got to tell you a dirty secret: nobody, in my opinion, has a great story for why more profitable beats less profitable. You can give a tautological behavioral story—that people underestimate how sticky profitability is, so when you buy the more profitable firms, it’s going to persist on average more—which I find plausible, but it’s pretty hard to test. The risk-based stories some have tried—I don’t buy them at all. But the empirical results, including a negative correlation with value (which boosts the attractiveness, certainly), are so strong that even in the past we would give it some weight, though probably less weight than if we had a great story to go with it. So it has always been a combination of the two. What I’ve said recently is that the advent of machine learning—which we’re using in a bunch of places, including to create some new factors (though “new” often means better ways to measure old ideas)—changes this balance. For example, if we want to see fundamental momentum, can machine learning, through natural language processing, extract a signal about fundamental momentum from corporate earnings statements or earnings calls? I won’t tell you how—we publish a lot, but there are limits—but we think the answer is yes. We still get a lot of intuition: we think that’s working for similar reasons to why fundamental signals always work. So we’re not doing something that’s purely data-driven. But are there steps in the process—I’ve used the term “surrendering to the machines”—where we lose some intuition, whereas in older methodologies we had intuition at every step? Yes, I think so. And the way you do this—and I won’t get too geeky for your listeners; Riccardo, I know you would enjoy it—is essentially that you represent every earnings call as a vector of numbers. A whole bunch of numbers. That’s what NLP does. Then, empirically, using more standard methods (you can get fancier too), you look at how these vector numbers predict returns going forward. It turns out it does a really good job. Nothing is anywhere near perfect, by the way, but it’s a really good job. It delivers a really nice Sharpe ratio for us and is correlated with some of the old fundamental measures. So you think you understand what it’s doing: it’s extracting information from these earnings calls about how things are going right now. And since language is nonlinear and complicated, ML does a better job than some old methods used to do, if you ask me. But if you ask me what it’s actually doing with those vector numbers—what the numbers mean—then I say, “You know, I’m really not sure.” And this bugged me for a while, and I’ve admitted I probably slowed us down by a year or two on some ML-based factors. And I think that was appropriate. When you’re going to do things that are different, that lean more on data and less on theory or intuition than the things that have worked for you for nearly thirty years, I think it’s appropriate to go slow. I’ve gotten convinced. And I’ll leave you with one last way to think about this, because it’s a very simple sentence but it was eye-opening to me—and embarrassing, because it’s obvious: if the ML part of your process didn’t involve some step that is not obvious or intuitive—if you understood every step perfectly—then what the heck is the ML doing? If it’s doing something that is easy to sum up with traditional, linear (or not necessarily linear, but traditional) methodologies, then it isn’t really doing anything. So the very act of using these tools implies a little bit of surrendering to the machines. Now, what has annoyed me is that when I’ve said this, a couple of reporters have written that “AQR has fully surrendered to the machines.”

RS:

No, no, of course not.

GUEST:

Points on a spectrum. Points on a spectrum. But yes: I think it has always been some of both, and when the empirics are strong—like in the profitability factor—we’ve always been willing to rely on some data evidence. Machine learning just requires being willing to have at least some step in the process that we understand a bit less than we used to.

RS:

Yeah, yeah. Before we part each other, just, an aspirational question, which is the typical one I ask to close my conversation with guests. If I’m not wrong, you have two couple of twins, right?

GUEST:

I have two sets of twins. My wife and I are now experts.

RS:

Two sets of twins. Great. Of course, the question is not about your family.

The question is if you had to give your 4 kids just one piece of advice on how they should invest their money over the long run, what would that be?

GUEST:

I told my children: if something happened to me — these stories always have this preamble — if AQR still existed and was run by my colleagues, stay there. Otherwise, something between Vanguard and DFA would be fine. Obviously, as a competitive person, I would prefer AQR. Also, I don’t charge my children fees, which is a nice advantage. A good manager is already hard to find, but one who doesn’t charge you fees is impossible.

RS:

Okay. Very special one. Great.

GUEST:

But if you don’t have access to what I do for a living, stay diversified. You don’t even need to do factor tilts: Jack Bogle’s pure approach would be perfectly fine with me. But if you find someone good — like my former professors — who can do factor tilts, and then you look at the portfolio every 5–10 years while you grow your family, that’s fine. It’s hard to do, but I hope they, my children, have seen what works over time and have an advantage.

RS:

Yeah. Clifford, thank you so much for your time. It has been a remarkable conversation, the one I had long waited for. Thank you for making it happen and my dream come true.

GUEST:

Thank you, I really enjoyed it. It was fun. You asked all the right questions. I hope to see you again soon.

RS:

I hope so.

Bye bye.

Welcome back to The Bull, your personal finance podcast.

Aside from a few giants like Warren Buffett and Gene Fama, the person most frequently mentioned on this podcast is probably Cliff Asness, the legendary former student of Fama and founder of the hedge fund AQR, the third largest in the world.

Why is that?

First, AQR is the firm that perhaps better than any other has managed to bridge academic financial theory with real-world application.

Second, Asness and his extraordinary team produce an impressive number of papers which—at least in my case—have probably contributed to about 50% of my overall understanding of finance.

In many episodes I told you that, come what may—and even at the risk of getting hit with a restraining order—sooner or later I would manage to bring Asness here with us.

At long last, this dream has come true, and the long conversation we had—rightfully earning the title of the longest episode in the history of The Bull—adds immeasurable value to this podcast.

So, even though he will never listen to this episode, thank you to Cliff Asness for this incredible honor, and thanks to all of you—because without your presence, and without being so many, this meeting would probably have remained just a mirage.

With Cliff we have talked about his years in Chicago under Fama and French, about why markets have become less efficient over time, about momentum and value, expected returns, trend following, and much more.

Without further ado, I leave you to my conversation with this extraordinary figure in global finance, Cliff Asness.

Enjoy the episode.

…

RS:

Cliff Thank you so much for being here.

GUEST:

Happy to do it, thank you for having me.

RS

You’re gifting us an incredible privilege by attending our podcast.

You can’t know it, but I’ve mentioned you and AQR’s work so many times here that you already belong to this podcast, without even knowing it adn long before your first appearance today!

GUEST:

Okay, well, that’s a little frightening, I gotta tell you, but it’s nice to hear.

RS:

One year ago, we hosted here your Grandmaster Gene. So it’s kind of a serendipitous occasion to have you here today, somehow the stars have aligned.

GUEST:

He’s the grand master, so you’re very lucky to have had him. He doesn’t often do things like that.

RS:

Yeah. It was remarkable.

And if you don’t mind, I’d like to start right from there. Would you tell us about your days in Chicago in the eighties and 90s? Back then you had the opportunity to study finance where Modern finance was born.

GUEST:

Yeah. I mean, whenever something works out. Well, you have to admit, you got lucky. At least partially. Few, few things, have no luck involved. And just being.

I started the PhD program in Chicago in nineteen eighty eight, and it was the late eighties and early nineties when Fama and French were really starting what today we might call factor investing. I always laugh because we didn’t have these terms back then. You always use today’s terms to describe the past, even though, you know, I don’t even think we called, like, the price to book, the value factor immediately. I’d have to go check exactly when that started, but I’m going to guess their first few papers didn’t. So I got lucky I was there, I got to work with them. I got to be early in something and that. And that is a lot of luck. I don’t think anyone, certainly including me at that point, thought, oh, this is going to develop into a major part of the investment industry. So yeah, it was phenomenal and, you know, it’s not just being there. It’s studying with those two men. Gene Fama. I remember I actually wrote a fair amount, not all of it, but a fair amount of my dissertation on what today we’d call the momentum factor. And I remember being very nervous about telling Gene, I want to write on this, because, you know, everything can be argued, but it’s not a very efficient market kind of factor. I mean, some people can try to make an argument that maybe this works for an efficient market reason. It’s hard. And I think I mumbled, you know, I want to study this price momentum factor, professor. And it worked very well because if it didn’t work very well, that is the Chicago Genpharma dissertation, because a lot of investors, a lot of, you know, Wall Street looks at things like momentum. So to be able to write tons of people claim to be outperforming, but a momentum really doesn’t work. It would have been beautiful. It would have been like, you know, stock splits aren’t a miracle would have just fit in perfectly. But I said this to Gene and his response, which I had feared. Well, his response was, if it’s in the data, write the paper.

RS:

Sure. Sure. Of course. Sure. Sure. I know the response. Write the paper.

GUEST:

One thing you learn from both Gene and Ken, is not that data should drive everything. Theory and intuition. And, you know, you have to avoid just overfitting. , but they respect data. they’re, you know, willingness to acknowledge, you know, farmers many times called momentum. I think he calls it like the key embarrassment to the five factor model, or something close to that. So it doesn’t matter what you like. It doesn’t matter what result you want to see. Respecting the result you do see is something I hopefully learned. I know those guys have it. I hopefully learned it, too.

RS:

Yes. I admit that when Fama came here last year, I tried to ask him about momentum, and his response was, “It’s not worth it.”

GUEST:

He’s honest about it, you know, and and and, you know, their model forms, like the scaffolding for modern finance. It’s hugely important, but no model is perfect or right. So, you know, I admit I’ve written.

RS:

Okay. Yeah. Yeah, some are useful.

GUEST:

Yeah, I have written that I think they should include momentum as a sixth factor. You’re allowed to disagree while still admiring. But, you know, Gene’’s quite honest about it, so I’ve always appreciated that.

RS:

Momentum is a challenge for the strong efficient market hypothesis because, as you mentioned earlier, it leans more toward the behavioral side when it comes to explaining the factor premium. Now my question is, in hindsight, what was incomplete in the pure efficient market hypothesis view, in your opinion?

GUEST:

Yeah, well, I’d like to, to even back up a little bit the pure efficient markets hypothesis. , even Gene. I don’t think he’d say markets are perfectly efficient. I think some, sometimes people overstate it, and they want to, you know, if someone believes markets are close to efficient, they’re they’ll paint Gene as more extreme than he is. I sat through his introductory first year PhD class three times, once as a student and twice as a teaching assistant. I went to every class because I was terrified to get something wrong. And, you know, sometime after teaching what the efficient market hypothesis is, Gene shocks the class by saying markets are almost assuredly not perfectly efficient because. Because Gene is brilliant and sane. Perfection is a silly hypothesis. I think Gene probably thinks they’re more extreme. More efficient than I do these days. I think I probably think they’re more efficient than the average day trader to go to an extreme. I don’t think most of us who are paying attention and trying to get the details right would have ever argued a pure, efficient market hypothesis. I do think, and I know you know the literature. Well in the ridiculous amount of years since then, I make a lot of comments about how old I feel when we go over these, these nineteen eighties kind of stories. Thirty seven years ago when I first met Gene. It’s been a long time, but in that period, a lot of empirical and theoretical results have tested, and you accurately talk about an efficient market explanation versus a behavioral one. We’re still fighting about almost all of them.There’s always going to be a story in one direction. You have to make a judgment on each one. Which explanation, you know, makes more sense to you?

And I think you’re right. Momentum is not impossible, but is much harder than some of the others to tell in an efficient market if a characteristic says this portfolio of one thousand stocks around the world should beat this other portfolio or does beat this other portfolio. There are always three possible reasons that can be true. One is accidental and overfitting. It just happened. It’s not going to happen again. Someone wrote a paper on it. If you get past that and I think, you know, certainly this is self-serving, but I think things like the value effect, the momentum effect now have such overwhelming evidence in so many places. I don’t give that a lot of credence, but you always have to have to have that one. So if something is real, it can work in an efficient market sense, because those things that outperform are riskier and you have to get paid for taking risks. And we could go down a rabbit hole of how to define risk. That is not simple either and is part of the issue.

But the other reason something can work is someone’s making a mistake. It’s not that these thousand stocks are riskier than these other thousand stocks, or the portfolio of them, to be more precise, is riskier. It’s that on average people overpay or underpay or something like that. And I do think again, to your point, momentum falls. It’s very hard to come up with something other than a behavioral explanation for moment of momentum would say value investing. It’s, , I think it’s closer to a battle. I admit, I’ve drifted more to the behavioral side over my career, but it’s still an interesting argument. It’s not a gimme either way.

RS:

Mm. Yeah. Definitely.

Last year you wrote a widely cited piece, The Less efficient market hypothesis, where you claimed that markets have become less efficient over time. Long story short, you do feel markets are still pretty efficient, at least for the average investor, but not that efficient as they used to be.

Could you please walk us through all of that?

GUEST:

Yeah, sure, first, I hope Gene’s not listening. I’m still scared of him when I say these things.

RS:

Do you still feel guilty for trying to beat the market?

GUEST:

Yeah, that was in my bio for a while. I don’t know if it’s still there. I’m scared that I’m trying to beat the market because Gene’s going to yell at me or something. Let’s go back to this, this idea that everyone who’s thought about it would agree. I think that markets are not perfectly efficient. Once you accept that kind of simple concept. Two questions. How inefficient are they and does this change through time become legitimate? Right. If things are not perfectly efficient, the you don’t know how inefficient they are and the idea that they will always stay the same amount of inefficient, it strikes me as kind of silly, so what I’ve observed over my career and I admit doing this stuff live and suffering the slings and arrows of some periods. where some of these factors we’re talking about were not rewarded. That is actually kind of a mild way to say viciously punished, two periods in particular, the what’s often called the dot com bubble in the late nineties.I say often called because if you just called the dot com bubble. You’re kind of giving away the story, because you’re using the bubble word. Not a good genpharma word. Right? If so, if you think it was a bubble, You know we wrote a lot on this at the time, and we revisited it over the years. If you take the basic Fama and French value kind of work, and you could do much more subtle versions of value than just, you know, book to price. But you see the effect no matter what you look at, a strategy based on buying cheap and selling expensive got crushed for about eighteen months. Like, you know, two and a half standard deviations, three standard deviations, kind of crushed, not ten standard deviations. We’re not talking about Nassim Taleb, Black Swan. Are there better or worse ways to measure this? But at least to my knowledge, to that point, no one had asked about how different the pricing was. Let’s keep it simple and just do a Fama-French price-to-book. Most people, including us, measure value a little differently these days, but if you sort stocks on price-to-book and go long the low multiples and short the high multiples, we thought an interesting question was: how different are the multiples? Does that change through time, and does that have predictive value? What we found was obvious: if you do this sort, the expensive ones always look higher-multiple than the cheap ones. I like to say your spreadsheet is broken if that’s not the case. The ratio, from memory, varied between three and six over time. The top third of more expensive stocks were sometimes about three times the price-to-book of the cheap stocks, and at the peak of the dot-com bubble they got up to about six times—again from memory, about twelve times.

RS:

Yeah. Crazy. A little.

GUEST:

Nothing similar had ever occurred before in fifty years of data. It was one of those embarrassing graphs; clearly something was going on. You could tell an efficient-market story where our measurements were missing something, or that the world had gone nuts. We also showed in that paper, which we still believe today, that these things are very hard to time. I wouldn’t bet my life on it. Even a few years ago I called it sinning to time these factors, and said you should sin occasionally and modestly. But over the long-term data we had, in the three-to-six range, when it was more extreme, value did better over the next few years and vice versa. That could have an efficient or a behavioral explanation. So at twelve, it looked pretty good, and that did work out. I did think that was a bubble; I didn’t think that was an efficient-market story. I wrote a piece called Bubble Logic in early to mid-2000 arguing this.

RS:

Good call.

GUEST:

I said: I don’t know how to define a bubble, but here’s my definition: if I can’t come up with assumptions in the ballpark of what I think are realistic that justify these prices, I’m willing to use the bubble word. In my view at the time, on very diversified portfolios, I would never use the bubble word lightly. Some people are promiscuous in how they use it, but for me a bubble also has to be market-wide and pervasive; it has to be about diversified portfolios, and this fits the criteria. If you had asked me back then to project forward into the next few years, say 2003–2004, I could have bragged that we had been right. The “round trip” was very profitable for us, even though we didn’t enjoy the first part at all. Those eighteen horrible months for value also happened to fall between the second and nineteenth month of my new firm, so that was not remotely fun. Momentum, during that period, did reasonably well, but not well enough to offset the disaster in value. We had argued that things would go very well afterward, and they did: the round trip was excellent. But if you had asked me after that full cycle, “Do you expect to see something this extreme again in your career?”—thank goodness no one did, because I think I would have answered incorrectly. I would have said highly unlikely. It had been the most extreme event in fifty years. And the question “in your career” implicitly assumes that you and your peer group are all still around. And if you’re still around, you’re probably the ones in charge. How could something like that happen again after you’ve already seen it once and are now the senior generation? I would have said no, very unlikely. And yet it happened again. Even before COVID—so roughly late 2019—the same kind of measure, done simply on price-to-book (though today you can use more diversified metrics), had come back very close to tech-bubble levels, with value suffering in a very similar way. And then, perhaps exceptionally, COVID hit and everything got worse. We blew past the extremes of the tech bubble in the spread between cheap and expensive stocks.

RS:

Me lo ricordo. Sì. La demo.

GUEST:

There was that absurd six-month period when the only stocks anyone seemed to “want to own” were Peloton and Tesla. It was not a pleasant time for people building systematic portfolios based on the value effect. So it happened again, and we survived. In fact, we ended up making money over the whole cycle, but it was extremely unpleasant for quite a while. Separately, we believe we’ve made our process more robust. If it happened again… even if we hadn’t made changes, we still love our process: it worked. It just wasn’t fun to live through. After the second time, the old phrase “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” applied. I was fooled twice, so shame on me. This made me ask: what did I miss? If I’ve lived through two bubbles in my career that were more extreme than anything seen in the previous fifty years, what hadn’t I understood? I started accepting again the empirical fact—which some may contest—that I had lived through two episodes I would call bubbles, more extreme than anything in the earlier data. I began to wonder why. And the piece I wrote, The Less Efficient Market Hypothesis, does not claim that markets are wildly inefficient or easy to beat, but that they are less efficient than they used to be.First of all, I wish I could correct something in that paper: that’s what I had in mind, but I don’t think I stated it as clearly as I could have. You always want to rewrite part of an old article. I even try to avoid reading them—or, no offense, listening to podcasts I’ve appeared on—because I just think, “Oh, I could’ve said that so much better.” The only time I listen to a podcast I’ve been on is when I have to go back on it, because I don’t want to tell Riccardo the exact same stories. But I started asking myself: why? If markets aren’t perfect and are subject—not necessarily to being less efficient every single day—but to being more prone to these episodes of “madness,” if you believe, as I do, that they were bubbles, then you have to start asking why. And in the piece, I hope I’m very clear that I’m making a hypothesis. We have two episodes. I like to joke: as humans we see too many crazy episodes in markets. As statisticians we see far too few. Give me a few hundred bubbles of comparable magnitude and maybe I can start telling you something statistically reliable about them and really test hypotheses—figure out what caused them. Two is not a big number to run tests on. But they happened. So I have a few—actually my two favorite—hypotheses, which I believe in.